Jessica Lu, spotlight editor

Captain Underpants has a new enemy, one much more ominous than the usual talking toilets and cafeteria lunch ladies. David Pilkey’s children’s series appeared at the top of the 2012 most challenged titles list, meaning parents and other adults were demanding the books be disallowed. “Offensive language” and “unsuitable for age group” were among the chief complaints. Unless these adults and I are speaking of two different Captains, I find this is further evidence that the “banned books list” reaps the consequences of the very censorship the First Amendment condemns.

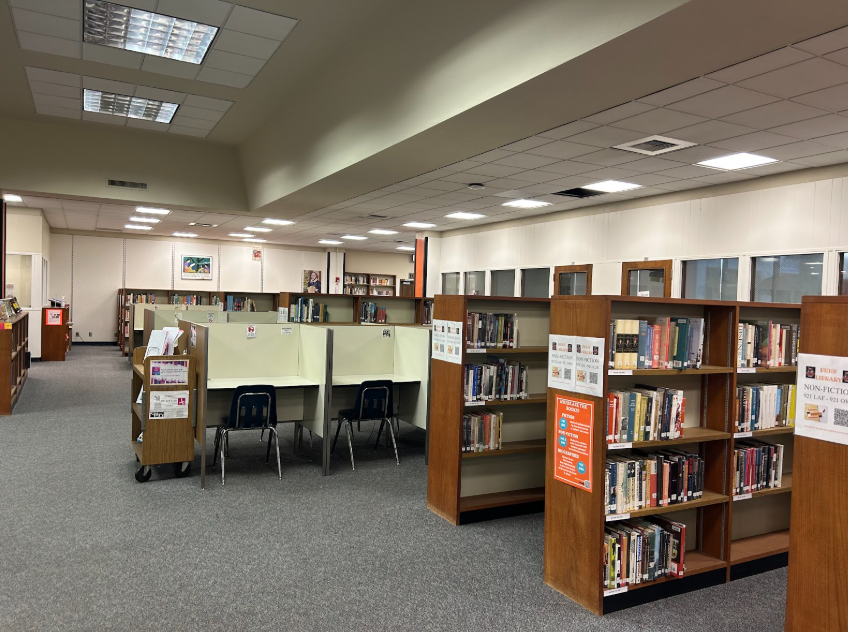

In light of Banned Books Week, which is Sept. 22-28, I traced the history of challenged books, shocked that titles like “Catcher in the Rye” and “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” reemerged year after year. I had overlooked the privilege of being unaffected by this censorship, even being required to read such books for summer reading. Yet millions of children in other states are being stripped of their right to read books we call classics, including “Gone with the Wind” and “To Kill a Mockingbird.” These are decisions primarily made by parents, according to the American Library Association’s (ALA) statistics.

Literature has always served as a window into the minds of its authors, transforming ideas into tangibility. We see history unfold not only through archaic writing styles but also through the depiction of previous lives. For instance, Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” has been decried for the appearance of the “n-word” and other “racist” components since 1885, a year after its publication. Be mindful that 1884 was only 26 years after the Emancipation Proclamation and 79 years before the “I Have a Dream” speech. Contextually speaking, discrimination toward African-Americans was rampant during Twain’s times, especially in previous slave states. The language was reflective of the vernacular, a depiction of race relations as Twain perceived it. Censoring the novel censors a contemporary portrayal of late 19th century attitudes.

It is not just historical eye-openers like “The Jungle” by Upton Sinclair and “The Grapes of Wrath” by John Steinbeck that provoke grown-ups. “Brave New World” by Aldous Huxley criticizes no specific time period, but is considered offensive for its sexual content and insensitivity. Sheltering kids from “Brave New World” ironically encourages the similar ignorance of the novel’s characters. If children are shielded from reading about sex, homosexuality or incest, chances are, they will be unable to respond to such concepts in a mature manner. Instead, today’s curious kid will turn to the randomness of the Internet instead of the intellectuality of a book.

Censorship closes books, which in turn closes minds. We constantly clamor for our other rights, but we still fail to address the basic right to freedom of expression. Banned Books Week is intended to inspire, to spread awareness and to advocate a return to the shelves, but its legacy should not last just seven days. It should serve a constant reminder to fight for the freedom to read. I envision a world in which Captain Underpants can fight wedgies without being bowdlerized.